Monarchy was for centuries the standard form of government in Europe. At the turn of the twentieth century only Switzerland and France had no sovereign as their head of state.

Whilst Switzerland had a long and proud tradition of local democracy, France vacillated between republican ideals and monarchical longings, alternating between presidents and kings of either Bourbon or Bonaparte extraction.

In the aftermath of the Second World War only a fraction of Europe’s royal houses were firmly entrenched on the throne. The First World War had seen the death of monarchy across Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman and Russian Empires. The Spanish ‘empire’ limped into the 1930s and the Second World War finished off the Italian and Bulgarian monarchies.

Today, monarchical systems of government in Europe are limited to the UK, Benelux, Scandinavia, Spain and the microstates. But what happened to the survivors and descendents of former ruling families? What happened to the families that survived the revolution?

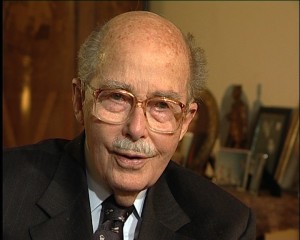

Otto von Habsburg, former Crown Prince of Austria-Hungary

The most prominent survivor of former royals was Otto von Habsburg. The Habsburgs were perhaps the leading European royal family. Austria-Hungary may not have been the richest, largest or most powerful European state, but it excelled in pomp, ceremony and protocol.

The Habsburgs were the preeminent European family, routinely Holy Roman Emperors and Archdukes of Austria, Kings of Hungary, Spain and Bohemia. Habsburgs had been Emperors of Mexico, a King of England and Charles V could claim to be a ‘world emperor’.

By the turn of the twentieth century the Habsburgs had consolidated their position as Emperors of the Dual-Kingdom of Austria-Hungary. All this would turn to dust in the aftermath of the First World War.

As a co-belligerent of the defeated Axis Powers, Austria-Hungary faced the settlement of the Peace of Versailles. The multi-ethnic, complex and disparate empire would suffer most for President Wilson’s concept of self-determination.

Of this single state, the countries of Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia would be created (which now, following further breakups, number at least seven countries). Left-over Imperial lands would be added to Romania, Italy, Poland and Ukraine.

Otto von Habsburg’s dignified and creative response to the vicissitudes of history ensured he would not become a bitter revanchist or dreaming monarchist. Instead, he used the heft of his family name to work hard for peace, human rights and a unified Europe.

He opposed the Nazi-led Anschluss of Germany and Austria and so riled the regime that Otto was sentenced to death in absentia and rendered stateless by Hitler’s personal revocation of his citizenship.

He served as a Member of the European Parliament (for the Christian Social Union in Bavaria) and led opposition to the communists (organising the Pan-European Picnic on the Hungarian-Austrian border in August 1989).

His death in July 2011 was greeted with widespread mourning throughout the former Habsburg lands. Despite Austria’s strongly republican constitution, Otto was given a funeral strongly reminiscent of imperial state funerals. The imperial overtones were supported by the service being presided by Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna, who was assisted by seven bishops from the various nations of Austria-Hungary.

Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, former Tsar of Bulgaria

Tsar Simeon II briefly succeeded Tsar Boris III as Tsar of Bulgaria in 1943. He reigned until 1946, when the country’s monarchy was overthrown by a Soviet-backed referendum. He would spend the next 44 years in exile, first in Egypt and then in Spain. The collapse of communism in Bulgaria in 1990 saw the new authorities grant Simeon a Bulgarian passport.

After a long delay he finally returned to Bulgaria in 1996, 50 years after the abolition of the monarchy. So far, this was a fairly typical experience of eastern Europe’s former ruling families. Simeon would make history, however, by returning once more to Bulgaria in 2001 and forming a political party (the National Movement Simeon II).

He went on to win the election in June 2001 and became Prime Minister of Bulgaria on 24 July 2001. His transformation from hereditary ruler to elected leader ensured his story was unique amongst Europe’s former monarchs.

House of Romanov, Emperors and Autocrats of All the Russians

The brutality and chaos of the Russian Revolution of 1917, the confused and bloody execution of the Royal Family at Yekaterinburg and the sheer size of the extended House of Romanov ensured that survivors and descendents of Tsar Nicholas II were scattered to the far corners of the earth.

Many found comfort in the close family connections in Britain whilst others put the old world firmly behind them by embarking on new lives in America and Australia. Prince Michael Andreevich did both – growing up in Windsor before

emigrating to Australia to work as an aviation engineer in Sydney.

Prince Vasili Alexandrovich Romanov also experienced life in Britain before emigrating to the USA in the late 1920s. His career was varied, spanning work as a cabin boy, shipyard worker, stockbroker, winemaker and a chicken farmer in northern California.

Prince Nicholas Romanov embarked on a business career before running a large farm in Tuscany, breeding cattle and producing wine. He also indulged in a particular favourite pastime of Romanovs – serial infighting and feuding over rights of succession to a non-existent throne and dead titles.

Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna is even more active on this front, actively campaigning for a restoration of the monarchy in Russia.

Manuel Braganza-Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, King of Portugal

King Manuel II of Portugal had a brief two year reign following the assassination of his father and elder brother in 1908. The assassination was a clear indication that all was not well in royal Portugal and in October 1910 a republican revolution erupted on to the streets of Lisbon.

Manuel was forced into exile, taking what would become a familiar path for deposed monarchs to end up in England. He was able to maintain a suitable household in Fulwell Park, Twickenham and spent his time researching Portuguese history and taking up good causes in connection with his Portuguese and Catholic background.

He had no children, and had decreed that the house of Braganza-Saxe-Coburg would die with him. Along with him would go any claim to the thrones of either Portugal or Brazil. This did not, of course, happen – there were enough separate branches of the royal family to produce claimants, and Dom Duarte Nuno emerged as the candidate with the strongest claim.

His son, Duarte Pio, Duke of Braganza, works as an agricultural development consultant and was a strong and vocal support for East Timorese independence.

Constantine – the King without a surname (former King of Greece of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg)

Constantine was King Constantine II of Greece from 1964 until 1973. His position following the abolition of the monarchy has been one of the most confused of any former king. He spent a portion of his reign in exile in Italy, and remained in Rome after the monarchy was abolished.

A referendum was held in 1974 on whether Greece should restore the monarchy or remain a republic, and the country overwhelmingly voted to retain the republic (with only 31% supporting a return of the monarchy).

Following the referendum, the Greek state and its former King have had stormy relationship. He was strongly discouraged from returning to Greece – on the death of his mother he was allowed to spend a few hours for her funeral at the former Royal Palace at Tatoi.

Legal wrangling engulfed his property holdings, and, in 1994, Constantine was stripped of both his Greek property and citizenship. He sued in the European Court of Human Rights for property worth over €550 million. His victory was bitter sweet – he was awarded only €4 million and the Greek government paid this out of its natural disasters fund, obliging the former king to pay the sum over to charities.

Perhaps the biggest anomaly is Constantine’s insistence that his family has no surname. Until 1994, his Greek passport identified him as Constantine, former King of the Hellenes. He currently travels on a Danish diplomatic passport with the name Constantino de Grecia. Greeks opposed to the monarchy refer to him as Mr Degrecias or Mr Glücksburg (in reference to the royal house).

His eldest son and heir apparent, Pavlos, is an experienced bluewater yachtsman and currently crews on the multi-record-breaking monohull Mari-Cha IV.