In my previous post I talked about the London Borough of Greenwich being elevated in status to a Royal Borough – an exclusive club with only three other members. The honour has been bestowed as part of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations. But is it a fitting accolade? What is royal about Royal Greenwich?

There is plenty of royal history in the borough with connections that stretch back centuries. The earliest records note that Edward I made offerings at the chapel of the Virgin Mary in Greenwich in the thirteenth century. His son, Edward II, was given

Eltham Palace by Bishop Bek of Durham for use as a royal residence.

Eltham continued in royal use for 300 years until falling into ruins as royal favour shifted decidedly northwards to Greenwich. From the sixteenth century onwards, royal presence in the borough focused exclusively on Greenwich.

Its royal manor was in existence by the time of Henry IV who wrote his will from there in 1408. Henry V

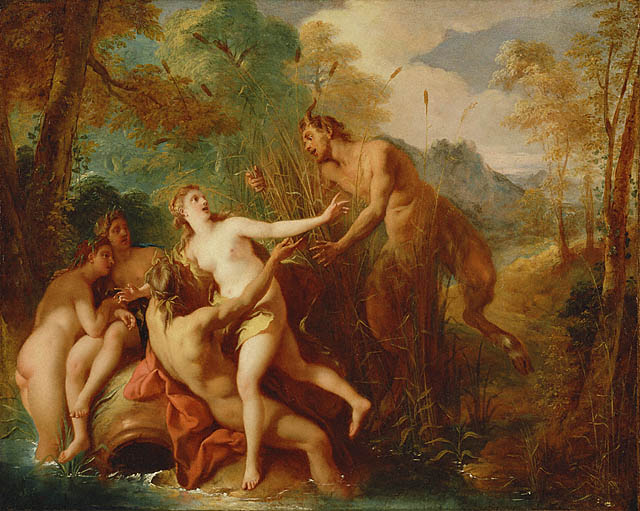

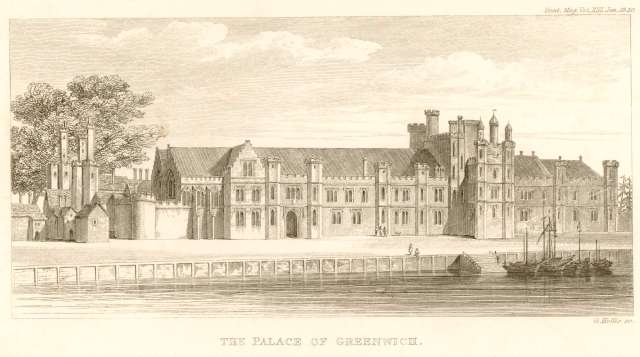

granted the manor to his half brother, Duke Humphrey of Gloucester, who built Greenwich Palace. Subsequent occupants renamed it

Placentia, the pleasant place, and it became a royal favourite for the next two centuries.

Placentia was the

birthplace of Henry VIII, Mary I and Elizabeth I and was much in use throughout the Tudor era. Easy access to the river combined with a pleasant aspect, decent hunting and a sufficient distance from the heaving masses in London made it a perfect spot.

After Elizabeth I, Greenwich lost its pre-eminent position amongst London’s royal residences. The

Queen’s House was built for James I’s wife, Anne of Denmark, but it didn’t receive much use before the English Civil War swept away any vestige of court life in Greenwich.

From the seventeenth century onwards, royal attention focused on Greenwich’s relationship with the sea. Royal dockyards sprung up along the Thames (the

Royal Dockyards at Deptford and Woolwich), building and servicing many of the Royal Navy’s ships of the line.

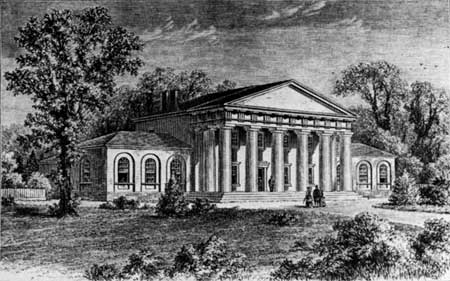

The crowning glory of Greenwich’s maritime links was the

Royal Naval College. This hospital, the maritime equivalent of the army’s Chelsea Hospital, was proposed by James II, established by Mary II and supported to completion by William III, Queen Anne, George I and George II. Subsequent monarchs donated paintings, money and patronage.

Whilst Greenwich is intimately connected to the sea, its eastern neighbour Woolwich is historically bound to our land forces. Woolwich is home to the

Royal Artillery Barracks, and hosted the Royal Artillery regiments for over 200 years from the start of the nineteenth century.

It was also home to the

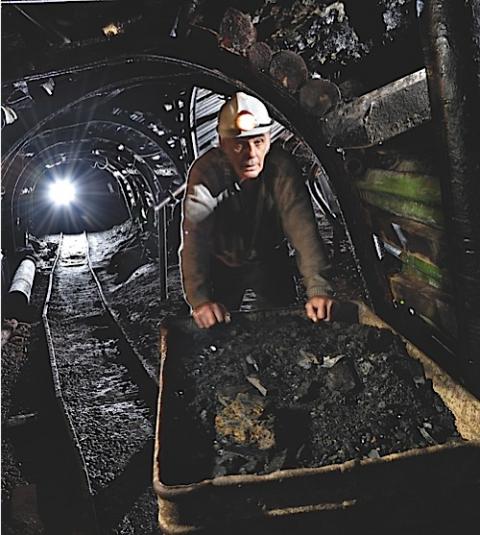

Royal Arsenal, with a history of armaments production and storage stretching back to 1671. The Royal Laboratory focused research into gunpowder and metallurgy whilst the Royal Brass Foundry produced high quality guns.

The final component of this considerably focused military complex was the

Royal Military Academy. The Academy, founded in 1741, aimed to produce good officers for the Royal Artillery and perfect engineers.

That takes care of royal connections to the sea and land, but there are even royal links to the sky. The

Royal Observatory is literally a crowning glory, sitting on top of Greenwich Hill and looking over the spectacular vista of the

UNESCO World Heritage Site and views across Docklands and London.

Whilst Greenwich’s role as a royal residence had ended, it still received more royal attention than most places. George I landed at Greenwich from Hanover on his accession in 1714 and the Duke of Edinburgh was made Baron Greenwich on his marriage to the Queen.

In addition to the palaces and institutions Greenwich has the following ‘royal’ streets:

Royal Place, SE10, Royal Hill, SE10, The Jubilee, SE10, Queen Anne’s Gate, SE10, Queen Elizabeth’s College, SE10, Queen Mary’s Court, SE10, King George Street, SE10, King John’s Walk, SE9, King William Lane, SE10

It also has a plethora of royal pubs:

Greenwich: The Crown, King’s Arms, the Prince Albert, the Royal Standard, the Royal George, the Rose and Crown, Richard I, the Star and Garter, Victoria

Eltham: The Crown, the Royal Tavern

Woolwich: Queens Arms, Prince Albert

Blackheath: The Crown, the Royal Standard

And finally a batch of random institutions:

Crown Woods school, Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Woolwich, Queen Elizabeth’s College in Greenwich (a set of alms houses, rather than a place of learning) and the Queen Elizabeth II Pier on the River Thames.